The Potential of RLMs

Handling Your Long Context Today & Designing Your Agent Tomorrow

Context Rot is the Worst Context Failure

“Context Rot” is a common problem agent designers must avoid and mitigate.

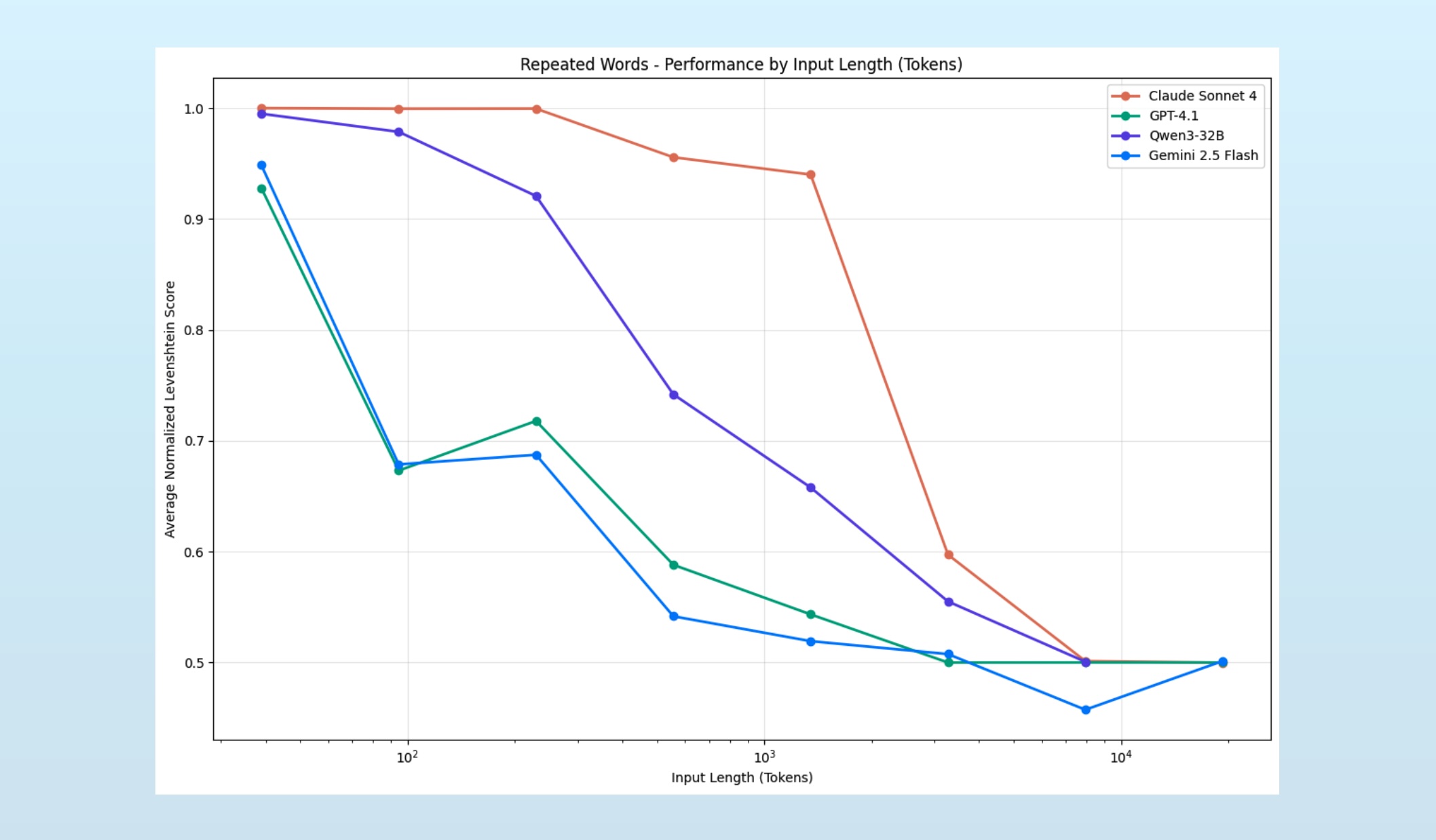

The Gemini 2.5 paper was one of the first technical reports that flagged the issue, noting that the performance of their Pokémon-playing harness rapidly deteriorated as the context grew beyond 100,000 tokens; a figure far below Gemini 2.5’s 1 million input token limit. We covered this in our context failures piece, but the Chroma team published the canonical exploration of the effect, dubbing it context rot.

A key takeaway from Gemini’s Pokémon troubles and the Chroma post is that context rot is not a capacity problem. It’s a quality problem. As the context grows beyond a model’s soft limit, the model continues to issue output as its accuracy declines. This makes for a pernicious problem, one that sneaks up on us the longer we run agents.

Of all the context fails, context rot is the worst.

Enter Recursive Language Models

Defined by Alex Zhang and Omar Khattab, Recursive Language Models (or RLMs) are a simple idea:

- Load long context into a REPL environment1, stored as variables.

- Allow an LLM to use the REPL environment to explore and analyze the context.

- Provide a function in the REPL to trigger a sub-LLM call.

That’s it. That’s an RLM. The LLM will use the REPL to filter, chunk, and sample the long context as needed to complete its task. It will use the sub-LLM function to task new LLM instances to explore, analyze, or validate the context. Eventually, the sum of the LLM’s findings will be synthesized into a final answer.

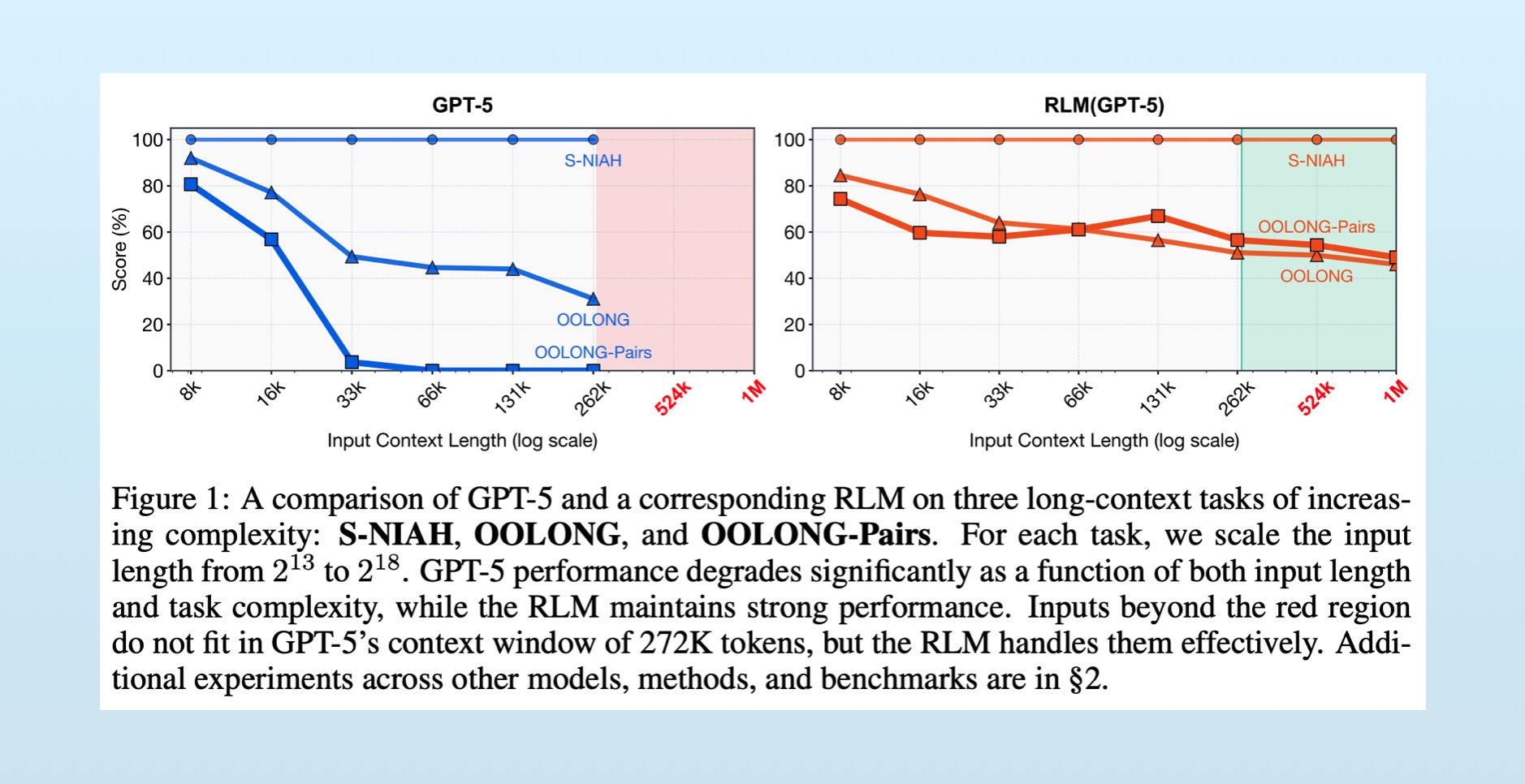

With this setup, the long context(s) can be really long. I’ve given RLMs logfiles more than 400 megabytes in size, with no issues. In the original RLM post, Alex reports that performance doesn’t degrade when >10 million tokens are provided.

Note the orange lines on the right: as the context length increases, performance very slowly degrades, hovering around 50-60%. Compare this to the non-RLM results (with the same GPT-5 model), which dramatically decline until failing entirely at 262,000 tokens.

RLMs Work By Turning Long Context Problems Into Coding & Reasoning Problem

The key attribute of RLMs is that they maintain two distinct pools of context: tokenized context (which fills the LLM’s context window) and programmatic context (information that exists in the coding environment). By giving the LLM access to the REPL, where the programmatic context is managed, the LLM controls what moves from programmatic space to token space.

And it turns out modern LLMs are quite good at this!

Let’s look at an example.

Here I’ve given Kimi K2 a very large dataset of Stable Diffusion prompts (prompts people provided to generate images). I then ask the RLM to identify the most common celebrities used in these prompts (and of course, I’m using RLM in DSPy). If you’re curious, here’s the code.

I give the RLM a budget of 5 iterations to accomplish the task. Below, you can swipe/page through each iteration, which shows the LLM’s reasoning and the code it executed in the REPL. There’s a few things to keep in mind as you read through:

- Every time the LLM calls

printin the REPL, it’s bringing new context into the token space. (I’ve omitted this output for brevity) - When the LLM calls

llm_query(highlighted in blue) in the REPL, it’s tasking another LLM instance with a sub-call. It stores the result of this function as a variable, usually. - On the last iteration, the LLM calls a special function

SUBMIT, which indicates it has finished with the task.

Click through and read, it really illuminates how a RLM works:

We can clearly see the LLM exploring and sampling the context, planning an approach, testing the approach, scaling the approach, then finally synthesizing its findings into a final answer. (In this case, it was correct!)

The context I gave this RLM – the collection of Stable Diffusion prompts – exceeds the maximum context window of any LLM. It would fail before it started, whereas a DSPy RLM harness around Kimi K2 took only a couple minutes.

It’s incredible, but with this example we can identify a couple limitations of RLMs.

First, it’s relatively slow. Answering this question took over a dozen LLM calls and several minutes. And we were using Kimi K2 on Groq. Try this with GPT-5.3 or Opus 4.6 and you’ll be waiting around even longer.

Second, as you read through the reasoning and code in the example above it becomes apparent that you need strong models to drive RLMs. Qwen3-30B-A3B couldn’t complete this task. It got confused, lost track of progress, and ended up running out of budget before submitting an answer2.

This brings us to the second reason RLMs work so well (in addition to maintaining the two token and programmatic context pools): RLMs exploit the coding reasoning gains of the last +18 months.

We’ve covered before how LLMs are getting better at verifiable tasks because it’s relatively easy to synthesize data and evaluate verifiable tasks, like math and coding. We’ve spent many billions of dollars post-training coding skills into frontier models. RLMs wrap long contexts in a coding environment so they’re addressable by the LLM’s incredible coding abilities, turning context rot into a coding problem.

Even better, RLMs get to use the REPL not just as a tool for exploring and managing long contexts, but also as a deterministic scratchpad. This proves to be a killer resource for many tasks. You occasionally see this benefit in action in ChatGPT or Claude, when the LLM will fire up a Python script to answer a question3. This hybrid capability of RLMs – the ability to use probabilistic, fuzzy LLM logic for some challenges and deterministic code for others – will likely become a stronger attribute as RLM harnesses mature and models are fine-tuned.

The Potential of RLMs: Agent Discovery Mechanisms

The ability of RLMs to mitigate the effects of context rot are really incredible. However, this isn’t the potential that excites me most. What excites me about RLMs is their ability to explore, develop, and test approaches to solving a problem.

If you start experimenting with RLMs (and I strongly suggest you should), be sure to continually review your traces. Set verbose to true and/or wire up DSPy to MLFlow. As you watch these models explore the context and try out different approaches (taking your iteration budget into consideration4), you’ll notice repeating patterns. In the example above, if I asked the RLM to find the top celebrities, aesthetic styles, or vehicles requested in the image generation prompts, it would repeatedly deploy similar tactics to situate itself and complete the task.

There is no reason we can’t identify these repeating patterns, decompose them, and optimize them.

This is what excites me about RLMs: if you run them on the same task several times, you’re generating emergent agent designs. These traces can then be used to explicitly define an agent, with higher reliability and lower latency. RLM passes discover the best approach to the problem, which we can then optimize.

The Limitations of RLMs

But if that’s the potential, how should you use RLMs today? In the last couple months I’ve seen teams use them for very large context scenarios, from general coding tasks across massive codebases to research and exploration across massive datasets.

At the moment, using RLMs on small context problems probably isn’t worth the squeeze. You’ll end up waiting around while the RLM explores context that could have simply been part of the prompt.

Further, RLMs do not solve other context fails, like context poisoning or context confusion. If bad information is in your programmatic context, there’s good odds it could influence the RLM in undesirable ways.

The Next “Chain of Thought”?

RLMs are slow, synchronous, and merely borrowing the current capabilities of models rather than leveraging models post-trained to be good at RLM patterns. There is so much low-hanging fruit here.

But that’s exactly what makes them exciting. Chain of thought was also simple and general (just ask the model to “think step by step”) and it unlocked enormous latent potential in LLMs, that was only fully realized through the creation of reasoning models. RLMs have the same shape: a test-time strategy that’s easy to implement today and will only get better as models are trained to exploit it.

You probably don’t need to rush out and refactor your agents today. But if your agents touch large contexts, start experimenting with RLM traces today. You’ll learn something about your problem…and you might discover your next agent architecture in the output.

-

“REPL” stands for “read-eval-print loop”. It is an interactive coding environment where one can enter arbitrary code and get back output. If you open your terminal and type

python, you’ll find yourself in a REPL. ↩ -

The team at MIT behind RLM has just released a version of Qwen3-8B post-trained on RLM traces. I hear it works pretty well, but no amount of fine-tuning or RL is going to help Qwen-8B code or reason as well as GPT or Opus. ↩

-

Both ChatGPT and Claude used to do this when asked, “How many R’s are in Strawberry,” though it appears both rely on reasoning or, in the case of ChatGPT, hide the previously visible Python code. ↩

-

I was continually amazed how well models would leverage their budgets. Kimi, in particular, wasn’t shy about ending early if the task proved simple. But it would also spend LLM sub-calls freely once it had a working approach, saturating my connection with Groq. ↩