How Long Contexts Fail

Managing Your Context is the Key to Successful Agents

As frontier model context windows continue to grow1, with many supporting up to 1 million tokens, I see many excited discussions about how long context windows will unlock the agents of our dreams. After all, with a large enough window, you can simply throw everything into a prompt you might need – tools, documents, instructions, and more – and let the model take care of the rest.

Long contexts kneecapped RAG enthusiasm (no need to find the best doc when you can fit it all in the prompt!), enabled MCP hype (connect to every tool and models can do any job!), and fueled enthusiasm for agents2.

But in reality, longer contexts do not generate better responses. Overloading your context can cause your agents and applications to fail in suprising ways. Contexts can become poisoned, distracting, confusing, or conflicting. This is especially problematic for agents, which rely on context to gather information, synthesize findings, and coordinate actions.

Let’s run through the ways contexts can get out of hand, then review methods to mitigate or entirely avoid context fails.

Context Fails

Context Poisoning

Context Poisoning is when a hallucination or other error makes it into the context, where it is repeatedly referenced.

The Deep Mind team called out context poisoning in the Gemini 2.5 technical report, which we broke down last week. When playing Pokémon, the Gemini agent would occasionally hallucinate while playing, poisoning its context:

An especially egregious form of this issue can take place with “context poisoning” – where many parts of the context (goals, summary) are “poisoned” with misinformation about the game state, which can often take a very long time to undo. As a result, the model can become fixated on achieving impossible or irrelevant goals.

If the “goals” section of its context was poisoned, the agent would develop nonsensical strategies and repeat behaviors in pursuit of a goal that cannot be met.

Context Distraction

Context Distraction is when a context grows so long that the model over-focuses on the context, neglecting what it learned during training.

As context grows during an agentic workflow—as the model gathers more information and builds up history—this accumulated context can become distracting rather than helpful. The Pokémon-playing Gemini agent demonstrated this problem clearly:

While Gemini 2.5 Pro supports 1M+ token context, making effective use of it for agents presents a new research frontier. In this agentic setup, it was observed that as the context grew significantly beyond 100k tokens, the agent showed a tendency toward favoring repeating actions from its vast history rather than synthesizing novel plans. This phenomenon, albeit anecdotal, highlights an important distinction between long-context for retrieval and long-context for multi-step, generative reasoning.

Instead of using its training to develop new strategies, the agent became fixated on repeating past actions from its extensive context history.

For smaller models, the distraction ceiling is much lower. A Databricks study found that model correctness began to fall around 32k for Llama 3.1 405b and earlier for smaller models.

If models start to misbehave long before their context windows are filled, what’s the point of super large context windows? In a nutshell: summarization3 and fact retrieval. If you’re not doing either of those, be wary of your chosen model’s distraction ceiling.

Context Confusion

Context Confusion is when superfluous content in the context is used by the model to generate a low-quality response.

For a minute there, it really seemed like everyone was going to ship an MCP. The dream of a powerful model, connected to all your services and stuff, doing all your mundane tasks felt within reach. Just throw all the tool descriptions into the prompt and hit go. Claude’s system prompt showed us the way, as it’s mostly tool definitions or instructions for using tools.

But even if consolidation and competition don’t slow MCPs, Context Confusion will. It turns out there can be such a thing as too many tools.

The Berkeley Function-Calling Leaderboard is a tool-use benchmark that evaluates the ability of models to effectively use tools to respond to prompts. Now on its 3rd version, the leaderboard shows that every model performs worse when provided with more than one tool4. Further, the Berkeley team, “designed scenarios where none of the provided functions are relevant…we expect the model’s output to be no function call.” Yet, all models will occasionally call tools that aren’t relevant.

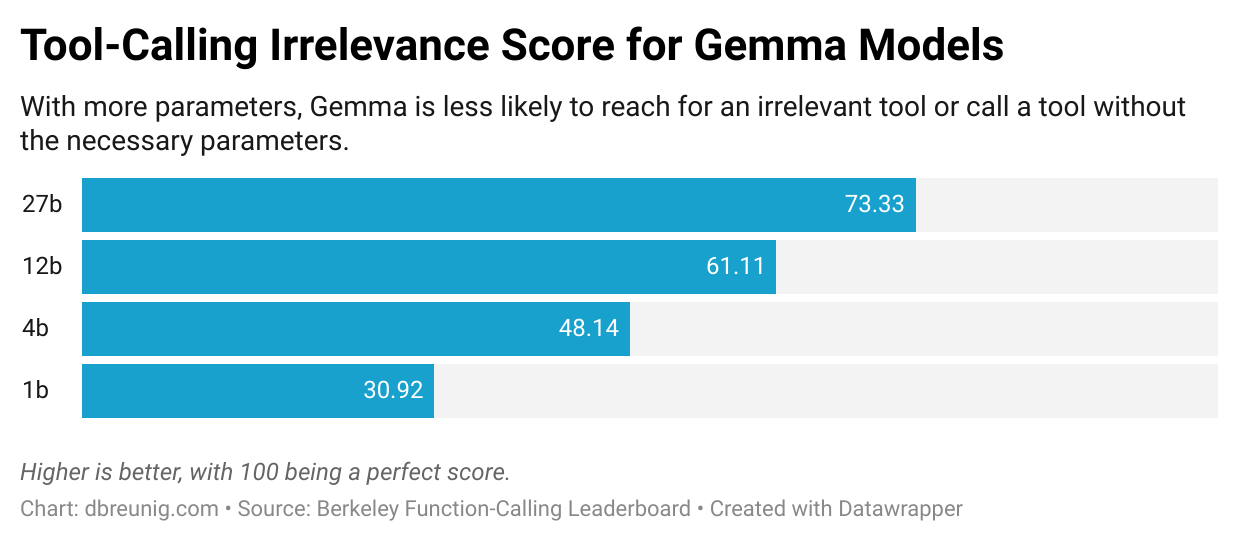

Browsing the function-calling leaderboard, you can see the problem get worse as the models get smaller:

A striking example of context confusion can be seen in a recent paper which evaluated small model performance on the GeoEngine benchmark, a trial that features 46 different tools. When the team gave a quantized (compressed) Llama 3.1 8b a query with all 46 tools it failed, even though the context was well within the 16k context window. But when they only gave the model 19 tools, it succeeded.

The problem is: if you put something in the context the model has to pay attention to it. It may be irrelevant information or needless tool definitions, but the model will take it into account. Large models, especially reasoning models, are getting better at ignoring or discarding superfluous context, but we continually see worthless information trip up agents. Longer contexts let us stuff in more info, but this ability comes with downsides.

Context Clash

Context Clash is when you accrue new information and tools in your context that conflicts with other information in the context.

This is a more problematic version of Context Confusion: the bad context here isn’t irrelevant, it directly conflicts with other information in the prompt.

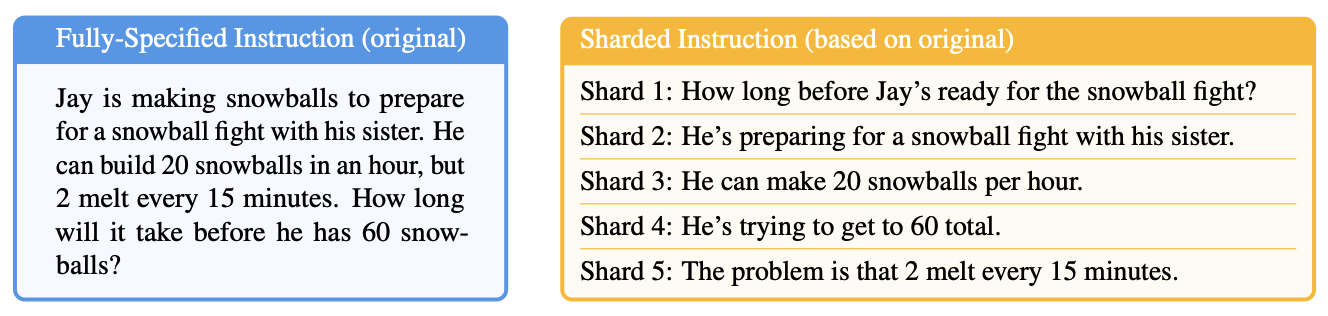

A Microsoft and Salesforce team documented this brilliantly in a recent paper. The team took prompts from multiple benchmarks and ‘sharded’ their information across multiple prompts. Think of it this way: sometimes, you might sit down and type paragraphs into ChatGPT or Claude before you hit enter, considering every necessary detail. Other times, you might start with a simple prompt, then add further details when the chatbot’s answer isn’t satisfactory. The Microsoft/Salesforce team modified benchmark prompts to look like these multistep exchanges:

All the information from the prompt on the left side is contained within the several messages on the right side, which would be played out in multiple chat rounds.

The sharded prompts yielded dramatically worse results, with an average drop of 39%. And the team tested a range of models – OpenAI’s vaunted o3’s score dropped from 98.1 to 64.1.

What’s going on? Why are models performing worse if information is gathered in stages rather than all at once?

The answer is Context Confusion: the assembled context, containing the entirety of the chat exchange, contains early attempts by the model to answer the challenge before it has all the information. These incorrect answers remain present in the context and influence the model when it generates its final answer. The team writes:

We find that LLMs often make assumptions in early turns and prematurely attempt to generate final solutions, on which they overly rely. In simpler terms, we discover that when LLMs take a wrong turn in a conversation, they get lost and do not recover.

This does not bode well for agent builders. Agents assemble context from documents, tool calls, and from other models tasked with subproblems. All of this context, pulled from diverse sources, has the potential to disagree with itself. Further, when you connect to MCP tools you didn’t create there’s a greater chance their descriptions and instructions clash with the rest of your prompt.

The arrival of million-token context windows felt transformative. The ability to throw everything an agent might need into the prompt inspired visions of superintelligent assistants that could access any document, connect to every tool, and maintain perfect memory.

But as we’ve seen, bigger contexts create new failure modes. Context poisoning embeds errors that compound over time. Context distraction causes agents to lean heavily on their context and repeat past actions rather than push forward. Context confusion leads to irrelevant tool or document usage. Context clash creates internal contradictions that derail reasoning.

These failures hit agents hardest because agents operate in exactly the scenarios where contexts balloon: gathering information from multiple sources, making sequential tool calls, engaging in multi-turn reasoning, and accumulating extensive histories.

Fortunately, there are solutions! In an upcoming post we’ll cover techniques for mitigating or avoding these issues, from methods for dynamically loading tools to spinning up context quarantines.

Read the follow up article, “How to Fix Your Context“

-

Gemini 2.5 and GPT-4.1 have 1 million token context windows, large enough to throw Infinite Jest in there, with plenty of room to spare. ↩

-

The “Long form text” section in the Gemini docs sum up this optmism nicely. ↩

-

In fact, in the Databricks study cited above, a frequent way models would fail when given long contexts is they’d return summarizations of the provided context, while ignoring any instructions contained within the prompt. ↩

-

If you’re on the leaderboard, pay attention to the, “Live (AST)” columns. These metrics use real-world tool definitions contributed to the product by enterprise, “avoiding the drawbacks of dataset contamination and biased benchmarks.” ↩