Claude's System Prompt: Chatbots Are More Than Just Models

A couple days ago, Ásgeir Thor Johnson convinced Claude to give up its system prompt. The prompt is a good reminder that chatbots are more than just their model. They’re tools and instructions that accrue and are honed, through user feedback and design.

For those who don’t know, a system prompt is a (generally) constant prompt that tells an LLM how it should reply to a user’s prompt. A system prompt is kind of like the “settings” or “preferences” for an LLM. It might describe the tone it should respond with, define tools it can use to answer the user’s prompt, set contextual information not in the training data, and more.

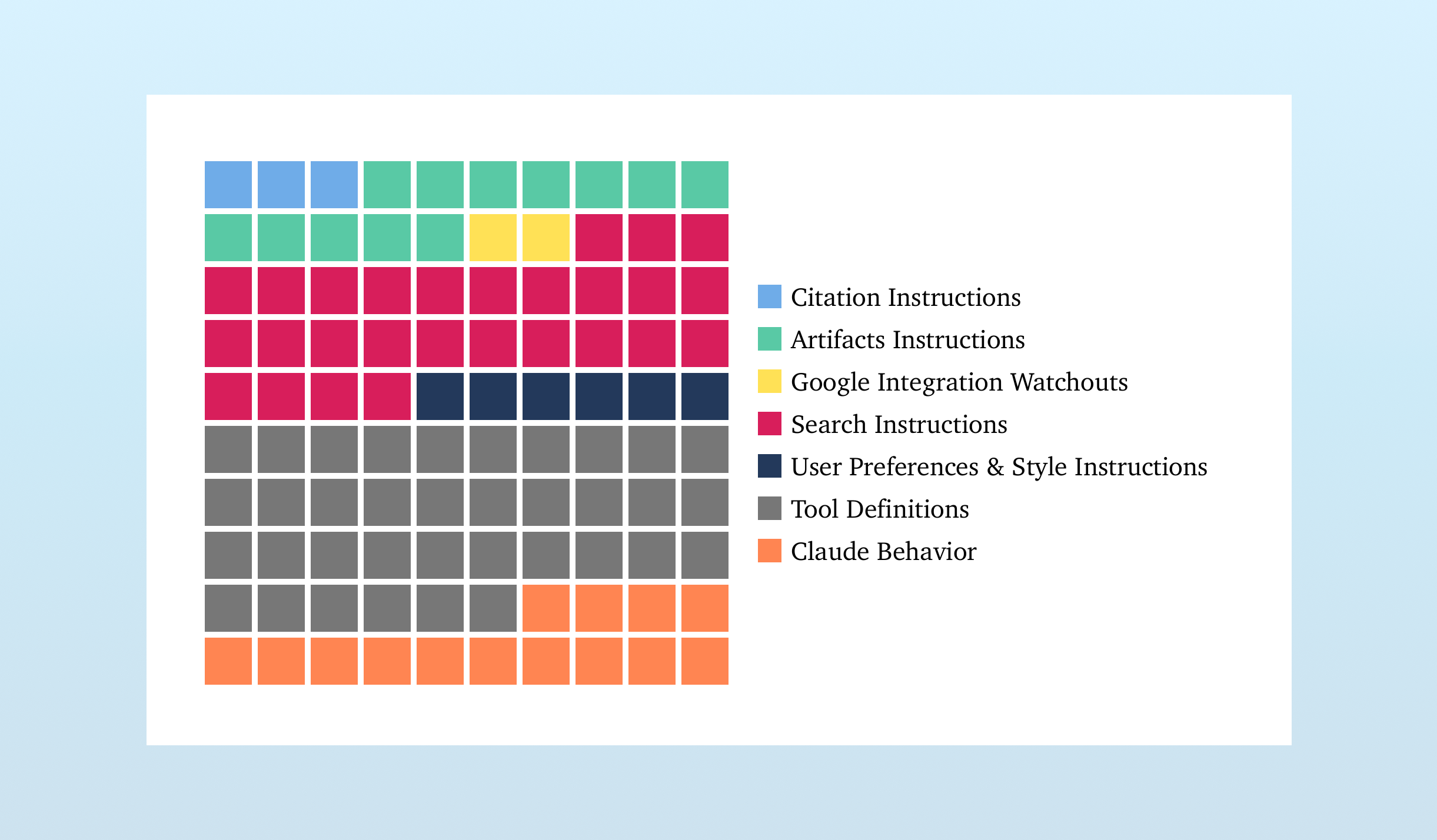

Claude’s system prompt is long. It’s 16,739 words, or 110kb. For comparison, the system prompt for OpenAI’s o4-mini in ChatGPT is 2,218 words long, or 15.1kb – ~13% the length of Claude’s.

Here’s what’s in Claude’s prompt:

Let’s break down each component.

The biggest component, the Tool Definitions, is populated by information from MCP servers. MCP servers differ from your bog-standard APIs in that they provide instructions to the LLMs detailing how and when to use them.

In this prompt, there are 14 different tools detailed by MCPs. Here’s an example of one:

{

"description": "Search the web",

"name": "web_search",

"parameters": {

"additionalProperties": false,

"properties": {

"query": {

"description": "Search query",

"title": "Query",

"type": "string"

}

},

"required": ["query"],

"title": "BraveSearchParams",

"type": "object"

}

}

This example is simple and has a very short “description” field. The Google Drive search tool, for example, has a description over 1,700 words long. It can get complex.

Outside the Tool Definition section, there are plenty more tool use instructions – the Citation Instructions, Artifacts Instructions, Search Instructions, and Google Integration Watchouts all detail how these tools should be used within the context of a chatbot interaction. For example, there are repeated notes reminding Claude not to use the search tool for topics it already knows about. (You get the sense this is/was a difficult behavior to eliminate!)

In fact, throughout this prompt are bits and pieces that feel like hotfixes. The Google Integration Watchouts section (which I am labeling; it lacks any XML delineation or organization) is just 5 lines dropped in without any structure. Each line seems designed to dial in ideal behavior. For example:

If you are using any gmail tools and the user has instructed you to find messages for a particular person, do NOT assume that person's email. Since some employees and colleagues share first names, DO NOT assume the person who the user is referring to shares the same email as someone who shares that colleague's first name that you may have seen incidentally (e.g. through a previous email or calendar search). Instead, you can search the user's email with the first name and then ask the user to confirm if any of the returned emails are the correct emails for their colleagues.

All in, nearly 80% of this prompt pertains to tools – how to use them and when to use them.

My immediate question, after realizing this, was, “Why are there so many tool instructions outside the MCP-provided section?” (The gray boxes above.) Pouring over this, I’m of the mind that it’s just separation of concerns. The MCP details contain information relevant to any program using a given tool, while the non-MCP bits of the prompt provide details specific only to the chatbot application, allowing the MCPs to be used by a host of different applications without modification. It’s standard program design, applied to prompting.

At the end of the prompt, we enter what I call the Claude Behavior section. This part details how Claude should behave, respond to user requests, and prescribes what it should and shouldn’t do. Reading it straight through evokes Radiohead’s “Fitter, Happier.” It’s what most people think of when they think of system prompts.

But hot fixes are apparent here as well. There are many lines clearly written to foil common LLM “gotchas”, like:

- “If Claude is asked to count words, letters, and characters, it thinks step by step before answering the person. It explicitly counts the words, letters, or characters by assigning a number to each. It only answers the person once it has performed this explicit counting step.” This is a hedge against the, “How many R’s are in the word, ‘Raspberry’?” question and similar stumpers.

- “If Claude is shown a classic puzzle, before proceeding, it quotes every constraint or premise from the person’s message word for word before inside quotation marks to confirm it’s not dealing with a new variant.” A common way to foil LLMs is to slightly change a common logic puzzle. The LLM will match it contextually to the more common variant and miss the edit.

- “Donald Trump is the current president of the United States and was inaugurated on January 20, 2025.” According to this prompt, Claude’s knowledge cutoff is October 2024, so it wouldn’t know this fact.

But my favorite note is this one: “If asked to write poetry, Claude avoids using hackneyed imagery or metaphors or predictable rhyming schemes.”

Reading through the prompt, I wonder how this is managed at Anthropic. An irony of prompts is that while they’re readable by anyone, they’re difficult to scan and usually lack structure. Anthropic makes heavy use of XML-style tags to mitigate this nature (one has to wonder if these are more useful for the humans editing the prompt or the LLM…) and their MCP invention and adoption is clearly an asset.

But what software are they using to version this? Hotfixes abound – are these dropped in one-by-one, or are they batched in bursts of evaluations? Finally: at what point do you wipe the slate clean and start with a blank page? Do you ever?

A prompt like this is a good reminder that chatbots are much more than just a model and we’re learning how to manage prompts as we go.

Update: Ásgeir Thor Johnson writes in to say he’s posted a new version of the system prompt, cleaning it up to make it more, “human-readable”:

I uploaded many files to try and make it kind of ‘human-readable,’ but this file is the one closest to the original. It’s probably more useful for power users, and I also include in it, as a comment at the top, some explanations on how to reproduce and all kinds of meta info.

There are various complications when getting Claude to write out the prompt. Deciding the best way to share the prompt has been quite a headache, which is the reason I have many files with the same system prompt in my repo. All of the info about this is in this new file in detail.