A Software Library with No Code

All You Need is Specs?

Today I’m releasing whenwords, a relative time formatting library that contains no code.

whenwords provides five functions that convert between timestamps and human-readable strings, like turning a UNIX timestamp into “3 hours ago”.

There are many libraries that perform similar functions. But none of them are language agnostic.

whenwords supports Ruby, Python, Rust, Elixir, Swift, PHP, and Bash. I’m sure it works in other languages, too. Those are just the languages I’ve tried and tested.

(I even implemented it as Excel formulas. Though that one requires a bit of work to install.)

But like I said: the whenwords library contains no code. Instead, whenwords contains specs and tests, specifically:

- SPEC.md: A detailed description of how the library should behave and how it should be implemented.

- tests.yaml: A list of language-agnostic test cases, defined as input/output pairs, that any implementation must pass.

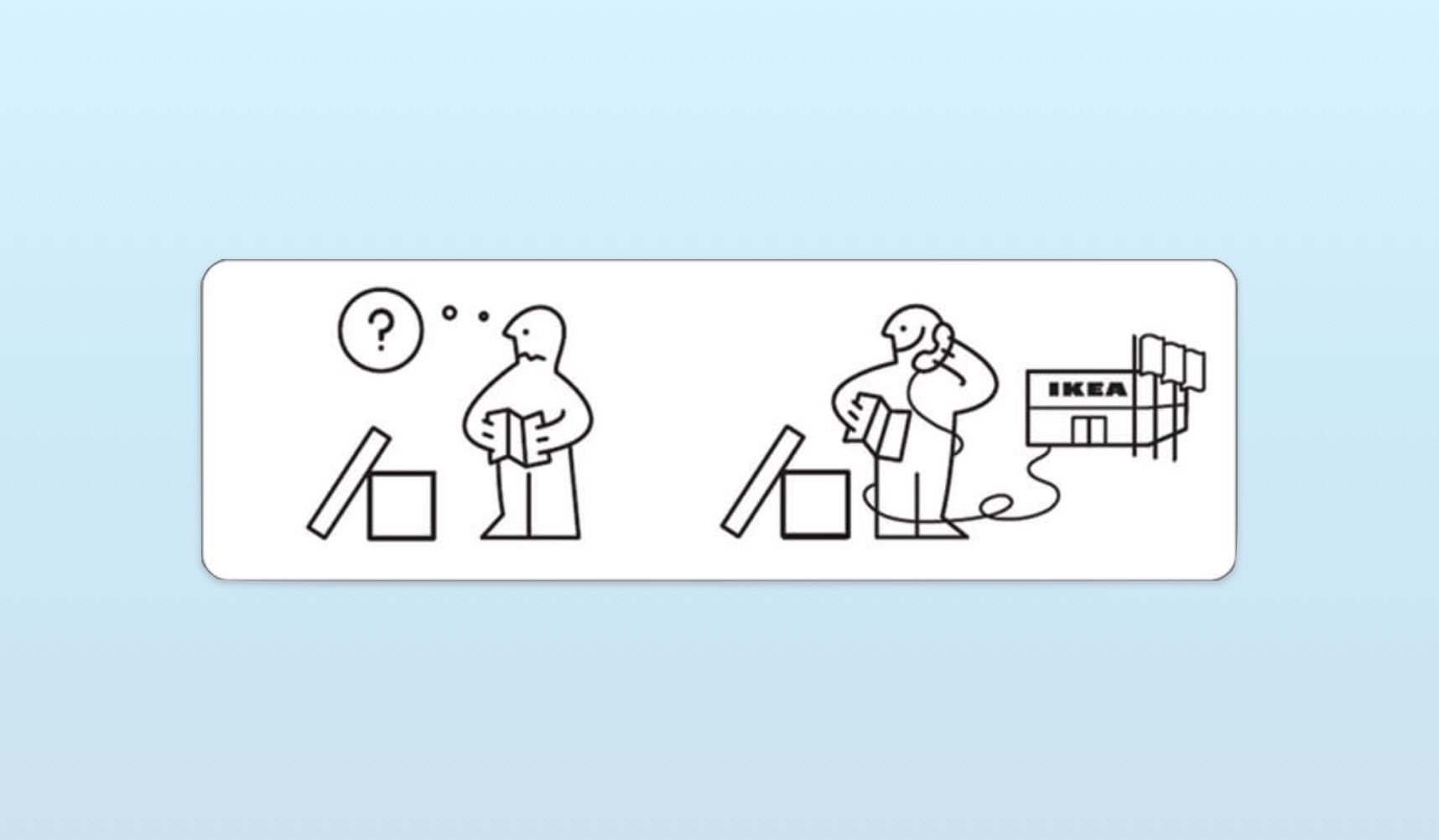

- INSTALL.md: Instructions for building

whenwords, for you, the human.

The installation instructions are comically simple, just a prompt to paste into Claude, Codex, Cursor, whatever. It’s short enough to print here in its entirety:

Implement the whenwords library in [LANGUAGE].

1. Read SPEC.md for complete behavior specification

2. Parse tests.yaml and generate a test file

3. Implement all five functions: timeago, duration, parse_duration,

human_date, date_range

4. Run tests until all pass

5. Place implementation in [LOCATION]

All tests.yaml test cases must pass. See SPEC.md "Testing" section

for test generation examples.

Pick your language, pick your location, copy, paste, and go.

Okay. This is silly. But the more I play with it, the more questions and thoughts I have.

Recent advancements in coding agents are stunning. Opus 4.5 coupled with Claude Code isn’t perfect, but its ability to implement tightly specified code is uncanny. Models and their harnesses crossed a threshold in Q4, and everyone I know using Opus 4.5 has felt it. There wasn’t a single language where Claude couldn’t implement whenwords in one shot. These capabilities are raising all sorts of questions, especially: “What does software engineering look like when coding is free?”

I’ve chewed on this question a bit, but this “software library without code” is a tangible thought experiment that helped firm up a few questions and thoughts. Specifically:

Do we still need 3rd party code libraries?

There are many utility libraries that aim to perform similar functions, but exist as language-specific implementations. Do we need them all? Or do we need one, tightly defined set of rules which we implement on demand, according to the specific conventions of a given language and project? For libraries that are simple utilities (as opposed to complex frameworks), I think the answer might be, “Yes.”

Now, whenwords is (purposely) a very simple utility. It’s five functions, doesn’t require many dependencies, and depends on a well-defined standard (Unix time). It’s not an expensive operation, a poor implementation probably won’t be a bottleneck, and the written spec is only ~500 lines.

But there’s no reason we couldn’t get more complex. Well defined standards (like those you’d need to implement a browser) can help you tackle complex bits of software relatively quickly. The question is: when does this model make sense and when doesn’t it?

Today, I see 5 reasons why you’d want libraries with code:

1. When Performance Matters

Let’s run with that browser example. There are well-defined, large specs for how to interpret HTML, JS, and CSS. One could push these further and deliver a spec-only browser.

But performance is going to be an issue. I want to open hundreds of tabs and not spring memory leaks. I want rendering to be quick, optimized to within an inch of what’s possible. I want a large group of users going out and encountering strange websites, buggy javascript, bad imports, and more. I want people finding these issues, fixing them, and memorializing them as code.

2. When Testing is Complicated

But Drew, you say, if we find performance issues in the spec-only browser we can just update the spec. That’s true, but testing updates gets complicated fast.

Let’s say you notice whenwords has a bug in its Elixir implementation. To fix the whenwords spec, you add a line to the SPEC.md file to prevent the Elixir bug. You submit a PR request and I’m able to verify it helps Claude build a working Elixir implementation.

But did the change screw up the other variants? Does whenwords still work for Ruby, Python, Bash, and Excel? Does it work for all of them when building with Claude and Codex? What about Qwen? Do we end up with a CI/CD pipeline that builds and tests our spec against 4 coding agents and 20 languages? Or do we just say, “Screw it,” and tell users they’re responsible for whatever code produced?

This isn’t a huge deal for a library with the scope of whenwords, but for anything moderately complex, the amount of surface area we’d want to test grows quickly. whenwords has 125 tests. For comparison, SQLite has 51,445 tests. I’m not building on a spec-only implementation of a database.

3. When You Need to Provide Support & Bug Fixes

Chasing down bugs is harder with spec-only libraries because failures are inconsistent.

Let’s imagine a future where we’re shipping enterprise software as a Claude Skill, or some other similar prepared context that lets agents implement our software for our customers, depending on their environment. This is basically our “software library with no code” taken to an extreme. While there may be benefits here, there are also perils.

Replicating bugs is nearly impossible. If the customer gets stuck on an issue with their own generated codebase, how do we have a hope of finding the problem? Do we just iterate on our spec and add plenty of tests, toss it over to them, and ask them to rebuild the whole thing? Probably not. The models remain probabilistic and as our specs grow the likelihood of our implementations being significantly different grows.

4. When Updates Matter

A library I like is LiteLLM, an AI gateway that provides one interface to call many LLMs across multiple platforms. They add new models quickly, push updates to address connection issues with different platforms, and are generally very responsive.

Other foundational libraries (like nginx, Rails, Postgres) push essential security updates. These are dependencies I wish to maintain. Spec-only libraries, on the other hand, likely work best for implement-and-forget utilities and functions. When continual fixes, support, and security aren’t needed or aren’t valued.

5. When Community & Interoperability Matter

Running through all the points above is community. Lots of users mean more bugs are spotted. More contributors mean more bugs are fixed. Comprehensive testing means PRs are accepted faster. A big community increases the odds someone is available to help. Community support means code is kept up-to-date.

When you want these things, you want community. The code we rely on is not just an instantiation of a spec (a tightly defined set of concepts, aims, and requirements), but the product of people and culture that crystallize around a goal. It’s the magic of open source; why it works and why I love it.

For the job whenwords performs, we don’t need to belong to a club. But for foundations, the things we want to build on, the community is essential because it delivers the points above. Sure, there may be instances of spec-only libraries created and maintained by a vibrant community. But I imagine there will continually be a reference implementation that codifies and ties the spec to the ground.

But the above isn’t fully baked. Our models will get better, our agents more capable. And I’m sure the list above is not exhaustive. I’d enjoy hearing your thoughts on this one, do reach out.