Why Media Metrics Matter

A Primer on Media Measurement and Why it Defines Your World

We sometimes treat the information industries as if they were like any other enterprise, but they are not, for their structure determines who gets heard.

— Tim Wu, The Master Switch

Advertising funds much of the information and entertainment in our lives. The amount of funding from ads each source receives is determined by media metrics. Media metrics help advertisers understand who is looking at their ads (if anyone) and what they’re doing after they see them.

Perform well against key media metrics and your media property will thrive. Fail to deliver and your newspaper, TV station, website, podcast, or newsletter will need to find money elsewhere.

Media metrics influence what information circulates because they determine which information sources gets paid. And content, like most anything else, follows the easy money.

What Are Media Metrics?

Media metrics tell advertisers if their ads are worthwhile. They answer questions, like:

- Are there people at the venue where I’m advertising?

- Are the people I care about at this venue?

- Are people seeing my ad?

- Are people interacting with my ad?

- Are people influenced by my ad?

- Are people taking action based on my ad?

Some of these questions are easy to answer. Some of them are nearly impossible. All of them are heavily contested and argued about due to the money involved.

Media metrics are tools marketers use in an attempt to answer one or more of the questions above.

In digital advertising, the most common media metrics are:

- Cost Per Click (CPC): How much does the advertiser have to spend to get someone to click one of their ads?

- Cost Per Action (CPA): How much does the advertiser have to spend to get someone to perform a predefined action? Often this is defined as a the audience buying something, signing up for something, or calling a phone number.

- Cost Per Install (CPI): A variant of CPA. How much does the advertiser have to spend to get someone to install an app?

- Cost Per Mille (CPM): How much does the advertiser have to spend for one thousand people to view their ad? (‘Mille’ just means thousand.) CPM is often defined by a target audience. For example, a marketer pays to deliver an ad to affluent Millennials.

There are many more metrics and new ones appear all the time. But most fail or are used by a handful of marketers for their own purposes. (Domino’s Pizza used “Cost Per Pizza Ordered” for years. They may still!)

Very, very rarely a new metric will be adopted by a sufficient number of marketers and media owners to become a currency: a common metric people use to buy and sell media. A currency creates a marketplace. It defines the demand present, incentivizing content producers to create things for it.

Currencies are the metrics you should be aware of and understand. They’re the metrics that shape our world.

Creating a Media Currency

There’s no clear moment when a metric graduates to become a currency. It happens slowly but predictably. More and more advertisers allocate funds to buy a new metric, driving more and more media outlets sell inventory metered by this metric. The metric becomes portable, liquid. A stable, recurring source of ad spending.

The creation of a media currency is a disruptive event in the marketplace. The dollars must come from somewhere. They’re either newly allocated marketing dollars (because the metric represents an entirely new type of opportunity) or shuffled from an incumbent currency (because the metric supplants existing tactics). Internal Marketing groups, media agencies, and publishers rise and fall when a new currency is crowned.

Because of this, new currencies are not easily created. Incumbent industries fight their emergence.

But this is how a currency is usually created:

Phase 1: Become a Shiny Object

Let’s say you create a new media property and/or social network and begin to acquire users and interest rapidly. Soon, your success can’t be ignored by media buyers. Your platform offers a unique experience, which cannot be measured effectively by existing media metrics. But that’s OK: your property is new, exciting, and hyped. It is a shiny object. Media buyers will buy ads to learn about the new format, impress their clients, and win awards.

Most advertising budgets contain a slush fund reserved for new opportunities. Some advertisers (Red Bull, Dove, etc.) use these dollars to create exciting campaigns, unhindered by usual requirements, to win awards or shift the brand’s image. Others treat this fund as a “test and learn” budget, a place where new properties or ideas can be executed with the goal of learning, not explicit marketing success. Either way, these are the funds which you’ll be courting. Let’s say you attract lots of them.

An influx in advertiser attention and money will challenge your new company. Suddenly, your platform will have two clients to keep happy instead of just one: your users and your advertisers. Maintaining focus on user happiness and growth while servicing advertisers will divide your already limited resources.

As if that weren’t difficult enough, the platform has a limited life as a shiny object. Eventually you will cease to be novel and ad buyers will demand performance against media currencies. You won’t be new, cool, or exciting forever. YOU can maintain your coolness, extending shiny object phase (For example, Vice held this note impressively long) but coolness always fades.

Side Note

The shiny object crowd just hit a massive headwind due to macro economy troubles, so their population will dwindle. The fun stuff without metrics is the first to budget to get cut in tough times.

Phase 2: Find a Metric That Fits

Before your platform loses its cool, it needs to find or create a media metric that properly assesses its worth and doesn’t work against its unique experience. It then needs to convince media planners and their clients that the new metric is worth adopting.

If a platform can’t create metric or can’t sell it to advertisers, media planners will evaluate the platform with existing metrics that will certainly paint it in an unflattering light.

To understand this tension — how being valued by the wrong metric can corrupt your platform — let’s first look at a company that successfully sold in a new(ish) metric that aligned with its product. Let’s look at Google search.

Google’s Cost-Per-Click Metric Fits Their Product’s Strengths

When Google entered it’s shiny object phase the dominant metric in digital ad buying was cost-per-thousand ads delivered, or CPM. Media properties were paid every time they showed someone an ad, regardless of the outcome. If Google stuck with CPM and never sold in a new metric, there would be a strong incentive to show users more pages and keep them on their site longer — in short, deliver worse search results.

Thankfully, Google adopted a lesser-used metric called cost-per-click (CPC) which billed the advertiser every time a user clicked on an ad, leaving Google’s site. This wasn’t difficult to sell to media buyers. The only limiting factors at the time were lack of organizational structure to manage ‘click’ campaigns and companies not knowing what to do with web traffic once they had it.

CPC aligned the incentives for Google, who was financially encouraged to be the most efficient search engine. The more you used Google to search, the more opportunities Google had to serve you the right ad. This resonant cycle unlocked a deluge of dollars for Google, growing them into a giant.

Side Note

You can (and many do!) argue that the CPC model is causing Google to ship a worse product today. A search results page today is often half ads, requiring the user to scroll before any non-sponsored results are visible. But that’s another discussion entirely…

While Google found a metric that fit, most platforms aren’t so lucky. Usually they invent metrics they’re unable to sell to the market or forget to find a metric at all. They wake up one morning and discover they’re no longer a shiny object, are being valued with measures they can’t perform against, and there’s little runway left. If there’s no time to find and sell the right metric (or the market isn’t buying the ones you have) your window for monumental success has closed.

Attempting to perform against existing currencies will undercut your platform, devalue what makes you unique, and lead you on a road to irrelevance.

This is what happened to Tumblr.

Tumblr’s New Ad Formats Aren’t a Substitute for New Ad Metrics

Tumblr had a particularly strong shiny object phase. The company was a poster child for 2010s-era Silicon Alley. It was a vibrant community with countless exciting projects emerging from it’s pages. It reeked cool. Brands wanted to be there. Corporations started their own Tumblogs alongside their campaigns and started to pester the company about advertising.

In response to this demand, Tumblr launched Radar: a featured space on it’s homepage curated by editors highlighting popular or interesting posts. Radar was also (eventually) an ad unit. Brands could purchase a Radar ad for $25,000 for 6 million impressions. But this allocation of impressions didn’t include any earned impressions generated by people reblogging the post. So the CPM of the ad dropped dramatically if you created ads people were inclined to share.

At first, this looks like a good model! The incentives were aligned for advertisers to create ads that felt at home on Tumblr, allowing Tumblr to generate revenue without driving away their users.

But there were a few things that doomed Radar ads to fail.

First, creating an ad people would reblog was hard. Tumblr users were creative and fickle, sniffing out in-authenticity with art student ease. Tumblr attempted to address this challenge by educating creative agencies and even offering their own in-house design services (most new networks had to do this do some degree, this wasn’t limited to Tumblr by any means).

Second, Radar wasn’t targeted to specific users or content. At any given time there was a queue of rotating Radar posts, with some percentage being ads. Posts rotated through users’ Radar, fulfilling the impression quota of the ads, without consideration for who the users were. Advertisers are generally not a fan of this, though for the high priced shiny object advertising Tumblr was engaging with at the time, this was fine for a bit.

But more importantly, Radar was an new ad unit not a new ad metric. Sure, CPM is a currency…but it is not a performance metric. CPM measures how many people you reach not the efficacy of the ads themselves. Radar was an ad format well suited to the shiny object phase (when ad agencies don’t care about metrics so long as they’re winning awards, learning, and/or making their client look cool).

Ads at Tumblr quickly expanded beyond Radar into ‘Promoted Posts’, where advertisers paid to insert their Tumblr posts into users’ dashboards. These were priced similarly, with the same CPM metric costs being diluted if people shared good ads.

But by this point, the shine was coming off Tumblr. And while they had new ad units that were well aligned with what users wanted from the platform, they nothing to show in terms of new ad metrics. Advertisers were now asking for proof the ads worked from both Tumblr and their agencies executing the buys. And Tumblr only had their diminishing novelty, Likes, and Reblogs — all of which were not denominating their ads.

Around this time, Tumblr sold to Yahoo. Tumblr’s young, mobile audience checked the strategic boxes Marissa Mayer needed to check to re-frame Yahoo to the market, justifying a $1.1 billion price tag despite a pittance of revenues.

After the acquisition, Tumblr finally created a metric by shifting to selling ads priced by ‘engagement’ — advertisers paid if their ads were Liked or Reblogged — but the market wasn’t having it. Too little, too late. Their shiny object status was truly gone (nothing like an acquisition to do that to you!) and they hadn’t created and sold a metric to the market.

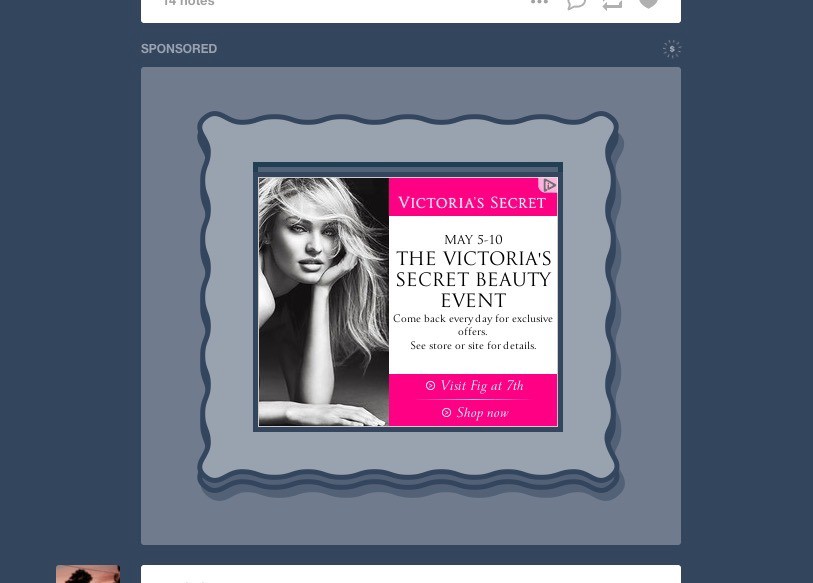

I knew decline was locked in for Tumblr when I saw this on my dashboard:

This is what capitulation looks like. Rather than a sponsored Tumblr post, this Victoria’s Secret ad is an IAB ad unit: an industry-standard digital display advertisement. The same ad format you’ll see on any other run of the mill webpage. Tumblr shoe-horned this into their dashboard with a quick blue frame, allowing them to adopt the ad units and metrics of the industry at large. They gave up creating a format and metric suited to their site and simply plugged into the broader, programmatic web. Sure, this gave them access to more money in the short term, but it guaranteed their unique platform would be valued in the same manner as any other blog, newspaper, or whatever. A race to the bottom had truly began.

Tumblr failed to create a metric that suited their unique platform before they lost their shine, denying the market an effective way to measure the true value of their platform. They (smartly!) sold before this problem was fully apparent, and eventually capitulated to existing metrics, built for other sites, to easily monetize the platform on the way down.

Most recently, Tumblr was sold to Wordpress for $3 million.

Phase 3: Crown a New Currency

If you can find a metric that aligns with your platform’s function and sell it to brands and ad agencies, you’re well on your way to something special. The flywheel is in motion. If you keep generating demand for your metric, at some point other platforms will take notice and adopt your metric to get a slice of the pie. Demand rises, then supply rises, and pretty soon you’ve got yourself a currency and the marketplace that comes with it. Waves of cash will engulf your platform as more advertising budgets allocate a line item for your metric.

Sometimes this happens early in a platform’s lifetime. Google’s CPC adoption certainly did. Other times it takes time and context changes to create the moment ripe for a new metric. This is what happened with Facebook, whose business truly took off once their mobile-install business took off, driven by the booming smartphone install base, a Cambrian era of mobile app businesses, and their cost-per-install (CPI) metric.

Side Note

Facebook had several failed pushes for new metrics prior to their CPI-fueled growth period. Notable was their eGRP effort, in partnership with Nielsen. GRP (gross rating points), created and manged by Nielsen, is the currency nearly all TV ads are denominated in. Billions of ad dollars of demand are out their buying GRP. Facebook, lacking a killer metric, partnered with Nielsen to translate this metric to the Newsfeed. If successful, they could have sold ads to GRP budgets, diverting a slice of TV ad spend to their platform. However, this was wishful thinking and never resonated with the market for multiple reasons. (Twitter tried this slight of hand as well. TV budgets are huge and super enticing…)

I believe this failure was actually good for Facebook. Borrowing an existing metrics not designed for their platform wouldn’t represent their unique value as well, as we saw with Tumblr. By bumbling along until they landed on CPI (which was partially due to them failing to spot mobile as the Next Big Thing!), Facebook didn’t capitulate to the value denominations of others.

This is the golden path of monumental platforms. They start by generating enough buzz to become a shiny object then use these funds to keep the company going while they try to establish a new metric that suits the platform. If they succeed, they create a currency and a marketplace, and are awash in ad dollars.

But while they bask in treasure and glory, a fourth phase begins…

Creating a currency defines demand in the marketplace. A currency highlights the existence of giant pools of money ready to buy anyone who can deliver against your metric. In short order, new companies will emerge built for the currency and existing companies will develop new ad units or features to get in on the funds.

Up until now, everything we’ve covered relates to the emergence of currencies and new media platforms. Once currencies are established, the exploits emerge. This is when the currency starts to affect our media environment and how we perceive the world.

After Google turned cost-per-click (CPC) into a currency, an entire industry emerged. Media owners adopted the metric and started to optimize their sites to get more clicks. Data-driven targeting, that worked across sites (so as to compete with the pristine signal Google had from user searches), blossomed into an entire sector. Search agencies become a thing, with armies of ad managers tweaking campaigns to get the lowest price per click. Botnets emerged, visiting sites and clicking on ads in increasingly convoluted fashions to evade anti-spam efforts. Everyone — ad buyers, ad sellers, tool providers — started gaming the metric. Fueled by easy money, denominated in CPC, the complexity and manipulation rose.

Media currencies are a spectacular example of Goodhart’s Law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

This would be a curiosity to most — a framework for understanding why some popular platforms thrive and others languish — if the gaming of these metrics didn’t significantly color the information to which we’re exposed.

Many online have a passing understanding of the “clickbait” concept, how content is published to perform against metrics advertisers will pay for. But the subtleties of other currencies are not fully appreciated. Metrics define demand, which define the ad formats created, which define the content being made.

Perhaps my favorite recent example of this effect is on YouTube.

To increase video views — one of the denominating currencies for YouTube ads — YouTube introduced mid-roll ads, or commercials in the middle of videos. YouTube only gets credit for video views if a viewer watches 10 seconds of it. Mid-roll ads generally check this box more effectively, as the viewer is already hooked on the content it’s inserted within when the ad runs. Contrast this with Pre-roll ads, which run before the content has started. Pre-rolls are more likely to drive off viewers within the first 10 seconds, as they’re not invested in the video much before it starts.

As a result of this new format, driven by the video views currency, YouTube creators started making longer and longer videos. Videos longer than 8 minutes allow creators to insert mid-roll ads, and it only goes up from there. As a result, we’ve now entered the golden age of video essays with creators creating content no less than 10 minutes and often longer than an hour. The ad metric drove the creation of the format, which drove the creation of the content, remaking the media landscape on YouTube.

As someone who enjoys longer form video essays, this is a great example of how tuned incentives — aligning currencies with the unique strengths of a platform — result in value for users, advertisers, and the platform. But not all currencies are as beneficial. And even the good ones age poorly over time, under optimization pressures from all sides.

For generations on the internet, people have warned, “If you’re not paying, you are the product.” Such an adage is good to keep in mind, but I suggest we take it a bit further. We should understand how we’re being packaged and sold so that we understand how it shapes the environments defined for us.