I Dream of the Post Office Buying Twitter

Does ‘Free Speech’ Include Distribution?

Yes, it’s a goofy dream. Yes, Congress won’t let them stop Saturday delivery, let alone spend $30 billion on a wobbly and weird social network. Yes, this will never happen. Yes, $30 billion could buy 90 F-35s instead.

But: I can’t get this idea out of my head. My mind stumbles on it every other commute. Every news item about Twitter’s sale spurs the notion. Google and Disney are walking away leaving only Salesforce, but oh: they just bought Krux. Maybe there won’t be a suitor. Their market cap is down to less than $15 billion on the news. Hmm, that’s only 44 F-35s…

Ok. This won’t happen. But the idea is so natural to me, so easily raised, that I feel compelled to share it with you. Perhaps doing so will expunge it from my head.

Here is why I keep dreaming about Twitter being bought by the USPS:

- It is becoming increasingly apparent that we, the people of the United States, expect Freedom of Speech to not only protect the articulation of one’s ideas and opinions, but the distribution of these notions as well.

- This expectation is shared by various political groups in the United States, from left and right, in various contexts.

- When Reddit banned it’s most reprehensible channels, protestors cried, “Freedom of speech!” Supporters of the move chastised the protesters for expecting that a private corporation should be required to host their content.

- When Facebook suffers a “technical glitch” and removes live broadcasts of police confrontations or protests, we wring our hands about freedom of speech again. When it’s not clear how trending news is determined, representatives from both parties demand clarification. All this happens despite the fact that Facebook is another private corporation which can host, or not host, whatever it wants.

- Hell, people were shouting about freedom of speech when that dude from Duck Dynasty was kicked off a TV show.

- The expectation that freedom of speech now covers some baseline of distribution is widely held among the US population. Pundits, congress people, journalists, and average citizens have come to expect information to be distributed to some degree.

- If we wish to fulfill this expectation, we have two options for ensuring this new concept of freedom of speech is guaranteed: we can make a deal with a corporation or develop the government’s ability to meet this need. Let’s look at an example for each.

- The best example for corporate negotiated information openness is AT&T. In 1913, AT&T struck a deal with the US government which ensured AT&T would not be pursued as a monopolist, so long as AT&T allowed competiting telephone companies to interconnect with their long-distance network. This, certainly, is a gross over-simplification, but everyone should just go read Tim Wu’s The Master Switch, which covers all of this, in context, beautifully:

We sometimes treat the information industries as if they were like any other enterprise, but they are not, for their structure determines who gets heard.

An AT&T-type deal, the dream of an idealistic monopoly, has happened many times (and a few times before). It is the default. It is what will likely happen with Facebook, Google, or whomever wins. Seriously, just go read Wu.

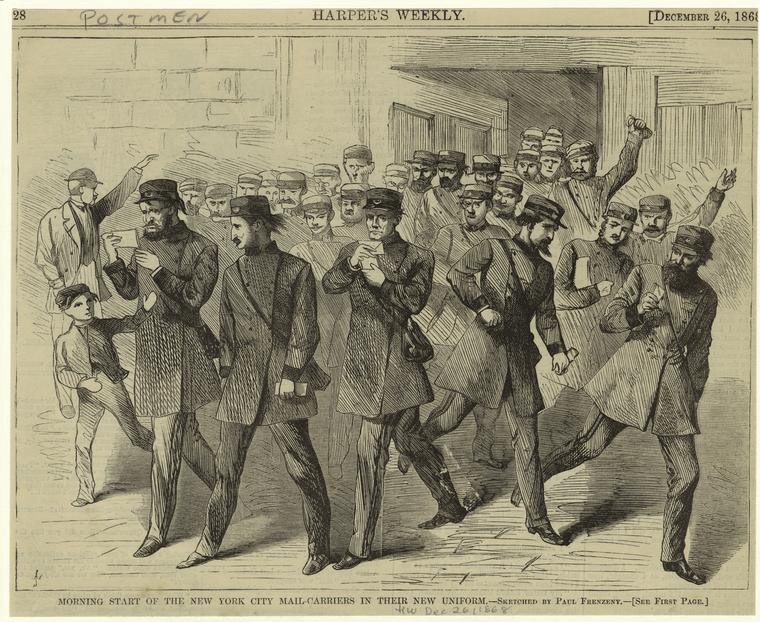

- But there is another model for information distribution: the government can take up the task. This is why we created the United States Post Office. The little discussed origins of the USPS was covered recently by Winifred Gallagher (here is an interview with a summary of her recounting).

- The USPS was instigated by our founding fathers during the 2nd Continental Congress. Ben Franklin was the first postmaster general. It is explictely authorized in the Constitution. Gallagher shows in her work that the motivation for it’s creation was to unite 13 different colonies, tying the nation together. Information, it was held, was crucial to the functioning of a democracy. If information could not be distributed, the new nation could not function.

- Both the corporate deal model and the government provided model have their pros and cons. A strong argument could be made for both. What worries me, what keeps this line of thinking alive in my brain, is that we aren’t having this discussion. We yell and protest when we feel some bit of speech must be distributed by Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, Google, or whomever. But we never stop and think about why *and if* we should be relying on private companies to guarantee the distribution of our speech.

- True, there are exchanges about net neutrality (coined by our good friend, Tim Wu) and we’ve had some victories, but we’ve had nothing approaching national discussion.

- If we do not discuss this, the choice is made for us: a deal with a corporation will be struck. We will ignore these issues while Facebook and Google continue to grow until one day we realize they’re too big and important to change or break up. Then, a deal will be cut.

- (Oh look: Facebook is working on bringing their own version of the Internet to rural and low income users for free.)

- Or: Twitter could flounder. No suitor could emerge while their market cap dwindles. At some point their price could become within the reach of a government take-over. Then digital distribution — for text, photos, video, conversations, and more — could be a public good, maintained by the public. Facebook could block whatever it wants. Google could remove search results and the stakes would be lower. The USPS could continue their mission of ensuring equal access to the distribution of information to the nation (should they care). And finally, our contemporary expectations of freedom of speech could be reflected by government guarentees. Yes, this is absurd. But it’s fun to think about. How would Twitter change under the USPS, assuming they had the resources to change Twitter? Real identities would need to be present, but not public. One could change their public name as one obtains a PO Box. Advertising would still be there, subsidizing development. The direct mail industry could move online, seamlessly shifting it’s household address databases to Twitter IDs for audience targeting. What new businesses would be unexpectedly fueled by this machine?

It’s a goofy idea, but one that spurs thinking.

Mock it if you like, but it’s much less boring than waiting quietly to strike a deal with Facebook.