The Business Implications of Machine Learning

It’s not about what it can do, but the effects of its prioritization

As buzzwords become ubiquitous they become easier to tune out.

We’ve finely honed this defense mechanism, for good purpose. It’s better to focus on what’s in front of us than the flavor of the week. CRISPR might change our lives, but knowing how it works doesn’t help you. VR could eat all media, but it’s hardware requirements keep it many years away from common use.

But please: do not ignore machine learning.

Yes, machine learning will help us build wonderful applications. But that isn’t why I think you should pay attention to it.

You should pay attention to machine learning because it has been prioritized by the companies which drive the technology industry, namely Google, Facebook, and Amazon. The nature of machine learning — how it works, what makes it good, and how it’s delivered — ensures that this strategic prioritization will significantly change the tech industry before even a fraction of machine learning’s value is unleashed.

To understand the impact of machine learning, let’s first explore it’s nature.

(I am going to use deep learning and machine learning interchangeably. Forgive me, nerds.)

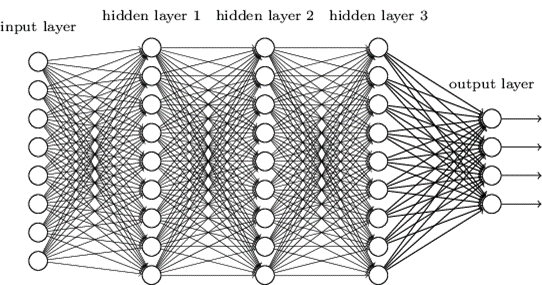

Machine Learning Makes Everything Programmatic

The goal of machine learning, or deep learning, is to make everything programmatic. As I wrote in January:

In a nutshell, deep learning is human recognition at computer scale. The first step to create an algorithm is providing a program with lots and lots of data which has been organized by humans, like tagged photos. The program then analyzes the bits of the raw data and notes patterns which correlate with the human organized data. The program then looks for these known patterns in the wild. This is how Facebook suggests friends to tag in photos and Google Photos searches by people.

So far, most of the deep learning applications people use are essentially toys: smarter photo albums and better speech recognition. These early applications are forgiving. If a learning algorithm misses a face or forces you edit a tricky word, it’s okay (usually). But as our investment continues and these algorithms become more dependable we’ll see them deployed in more interesting environments, with more interesting use cases.The takeaway here is the machine learning allows companies to build better applications that interact with things people create: pictures, speech, text, and other messy things. This allows companies to create software which understands *us. *The potential is there to solve the user interface problems that’ve been keeping people from computing since the Eniac. And major UI advancements tend to kick off major eras of computing.

The mouse and graphic interfaces made computers accessible, household objects.

Touch interfaces made computers normal, everyday tools.

Interfaces powered by machine learning will make computing omnipresent. (Eventually)

But there’s a catch:

Machine Learning is Only as Good as its Training Data

To make a machine learning model you need three things, in order of importance:

- Training Data: Data which has been tagged, categorized, or otherwise sorted by humans.

- Software: The software library which builds the machine learning models by evaluating training data.

- Hardware: The CPUs and GPUs which run the software’s calculations. Hardware is easy enough to acquire. Rent it, buy it, whatever.

Software is even easier to acquire! If you rented, you may have accidentally done so already. If not, almost all of it is available free.

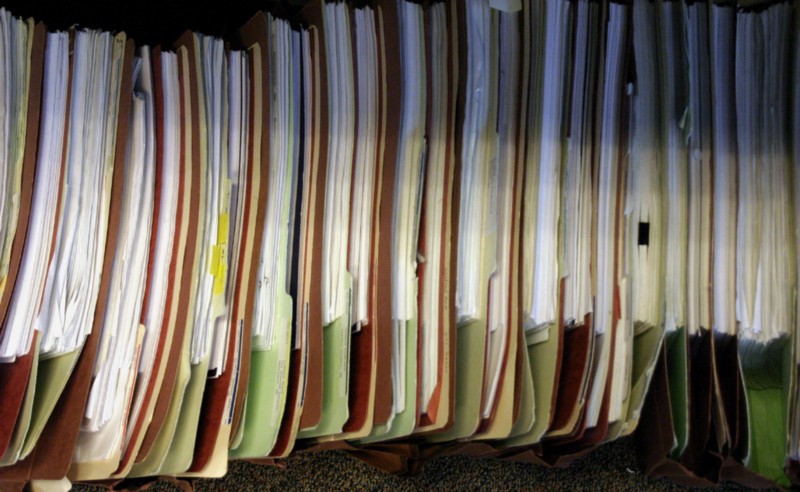

Now all you need is training data. And lots of it!

Good luck.

Before we get into how exactly screwed you are, let’s first understand why you need so much training data in the first place.

Our deep and machine learning software is good. Better than it was! But to work well it requires tons of training data to produce good results. This cannot be overstated: the quality of the models you make is directly correlated to the quantity and quality of the training data the software intakes. Until we have better software we’re unable to build good models from small datasets. (And when I say “small” I mean, not ginormous.)

Unfortunately, better software is not going to arrive overnight. While most software gets incrementally better, as developers squash bugs week by week, machine learning will likely advance in a punctuated equilibrium fashion: in a few, hard-won, big leaps.

The reason for this is deep learning software is nearly impossible to debug because we don’t fully understand how it works. To me, this is the weirdest thing about machine learning. We don’t really know what makes it tick. We can’t debug it systematically, we can only guess and check.

Pete Warden, machine learning evangelist extraordinaire, explains:

Even though the Krizhevsky approach won the 2012 Imagenet competition, nobody can claim to fully understand why it works so well, which design decisions and parameters are most important. It’s a fantastic trial-and-error solution that works in practice, but we’re a long way from understanding how it works in theory. That means that we can expect to see speed and result improvements as researchers gain a better understanding of why it’s effective, and how it can be optimized. As one of my friends put it, a whole generation of graduate students are being sacrificed to this effort, but they’re doing it because the potential payoff is so big.Until we understand how deep learning works, we need to make up for its inadequacies with big piles of training data.

Training data is the lifeblood of machine learning.

So how do we get it?

Learning to Use Every Part of the Buffalo (or User)

If computers are to understand messy, human things they need to be taught by messy humans. Makes sense. But when we remember how much data we’re going to need to make our models, we’re faced with a challenge: where are we going to find tons of people willing to spend their spare time to create our training data?

If you said, “I’ll hire them,” I have some bad news. At this scale paying them is pretty much out of the question.

If you said, “I’ll trick them,” you’re getting warmer.

A frequent refrain among people who write about the Internet is: “if you’re not paying, you’re the product.” These writers are commenting on ad-supported products — like Facebook, Google , Tumblr, SnapChat, and most everything else online— that package up your attention and sell it to advertisers. But their refrain works just as well for machine learning.

Users of free services are the humans who will train computers in order to build better products and services. The ‘free’ part is crucial because it allows for the massive amounts of users which our data needs require.

All of this makes me think of the old line about Native Americans using every part of the buffalo. Online services are learning how to use more parts of their users. Our attention creates their advertising and our knowledge fuels their deep learning models.

The trick to obtaining sufficient training data, then, is twofold. You need to:

- Attract a bunch of people.

- Convince them to create your training data. It’s Tom Sawyer and picket fences, just multiplied by several hundred million.

The Rise of Reciprocal Data Applications (RDAs)

A new category of application, or application feature, has emerged to facilitate your fence painting. These applications are designed to spur the creation of training data as well as deliver the products powered by the data captured. People get better apps and companies get better data.

The clearest example of such a reciprocal data application (or RDA, for short) is Facebook Photos.

Facebook Photos has been designed to prompt viewers to tag people in photos, easily and quickly. A clear call to action frames the faces of your friends and family after uploading an image. Tagging provides clear benefits to you, both for later searching and alerting those tagged in photos. Tagging garners attention and starts a conversation, which (non-coincidentally) are two of the main reasons why people use Facebook.

Meanwhile, all this tagging creates a massive pool of training data which can be used to train machine learning models. With better models, come better tagging suggestions and other features. Thanks to this RDA, Facebook likely has one of the best human image recognition models in the world.

Google Search is another RDA. Your searches and selections provide training data to Google, which helps make its search even better.

Like their other products, both Google Search and Facebook Photos demonstrate how RDAs generate significant network effects. The more people use an app, the more data is generated, the better the app becomes, the more people use the app…

Network effects are the engine needed for venture-backed companies in winner-take-all markets. Previously, the default network effect methods in the Valley was social/chat (you go where your friends are) or marketplaces (sellers go where the buyers are). This is why almost every non-marketplace venture-backed app or service shoehorns in sharing or communication features — even if it didn’t make sense in the app.

RDAs are a new method for creating network effects which is just now becoming understood. As awareness of its business value grows, expect RDAs to propagate throughout the landscape.

This propagation of RDAs will be the first major business impact of machine learning. Not only because they’ll divert resources, but because the qualities and requirements of of RDAs will influence the hardware and software which deploy them.

Here are the qualities of a Reciprocal Data Application:

- Apps must be networked, preferably always. Otherwise, it cannot send the data it captures back home.

- Nearly all computation takes place off-device. The bulk of computation is the creation of the models, which requires access to the massive dataset created by all users. Hence, model construction cannot take place on the device. Comparing new data to computed models (for example, identifying an object or person in a picture or recognizing a spoken phrase) is computationally cheap.

- Good apps need big audiences. More people equals more workers creating training data.

- Good apps need lots of usage. More time spent using the app means each user has more opportunities to create training data.

- Good apps encourage the creation of accurate data. If an app is designed in a way that coding errors occur often, the data will be weaker. App design needs to make it easy for users to enter accurate data, quickly. So how do we build good one?

Paths Toward Building a Valuable RDA

The data value of an RDA can be expressed as a product of the latter three points above.

For example, you can have a relatively meager install base if those users spend hours a day coding data in a reliable fashion (see: Tinder, who’s sitting on an amazing training set of data to determine the attractiveness of photos). Or, you could have a giant install base which only occasionally codes data (Facebook, whose users tag photos usually when they’re uploaded).

The challenge here is that qualities #3 and #4 are a zero sum game (like advertising, the other part of the buffalo). If 50% of the world spends 20% of their time on Facebook, there’s not very much oxygen left for you to work with. Even if you scape up a few hundred million users and borrow 2 minutes of their daily time, Facebook’s data collection will outpace whatever gains you make by many, many factors. Because data is collected constantly, the value of RDAs should not be thought of in absolute terms but as a velocity.

But, if in the above scenario you’re able to collect training data from your users Facebook cannot collect by design you cannot be outpaced, despite your smaller size. Small companies and other upstarts must pursue unique datasets if they want to compete.

We can see three paths towards building a valuable Reciprocal Data Application:

- Get Lots of People: Create a compelling app that attracts tons of users. This is the model the Valley knows and loves. Build something disruptive, gain traction, and invest like hell to go big. In a way, this path is the accidental RDA path. Once big, tweaking your app to better collect training data is merely a way to diversify the value you gain from your users. This path is ridiculously hard and requires a ton of luck, then a ton of money. Plus, it’s kind of a catch 22. Once you’re this big, advertising is likely the lower hanging fruit. You probably shouldn’t choose this path.

- Get Lots of Time: Create an app that convinces a reasonable amount of people to spend an extraordinary amount of time using it. In many cases, these sorts of apps or services will passively used. Think a navigation app that captures driver input or an always-on digital assistant. Ambient apps are always available to observe or prompt users, increasing the velocity of the data they produce.

- Collect Unique Data: Create an app which collects training data others can’t collect. Here, your app doesn’t need to be massive at launch, but a vision must exist for how the unique data you collect will later be used to build completely unique functions. These new functions need to be compelling enough to drive increased installs and usage to keep the velocity of your RDA sufficiently high prior to a large competitior changing the design of their apps and entering the market. This is how you might outrun Google and Facebook. You may have noticed that path #2 suggested examples which might not run on smartphones. Good eye! By taking computing into new contexts we can create RDAs which are more persistent, increasing the time spent with them. Better, these new contexts bring access to new types of data, which often merges path #2 into path #3.

Thankfully, since nearly all the functional value of RDAs is produced by far away servers crunching on massive datasets, individual devices have very little to do. Their brains are elsewhere so they can fit in more places.

How Machine Learning Impacts Hardware

With most of the thinking taking place in server farms, devices which deliver RDAs can be low powered. Their CPUs can be slow, since comparing input to pre-calculated models requires little computation. Slower CPUs can be small, since they require less transistors and less heat dissapation. And slower CPUs require less power, meaning batteries can smaller (or remain the same size and spend their capacity elsewhere, like on cellular connectivity). Plus: they’re cheap!

All this means devices which can deliver RDAs will propogate madly. If we can fit a cheap computer with wifi into a product and capture good data from that context we probably will build it. RDA capable computers will be injected everywhere: in your car, on your wrist, in your browser, through your portable speakers, in your TV, and more.

The purest example of this is the Pebble Core. Positioned as a device for run tracking and music, the Core is really more of a generic computing dongle. It’s cheap, starting at $69. It has a low-powered CPU, WiFi, cellular connectivity, Bluetooth, a bit of storage, a headphone jack, two buttons, and a battery. That’s it. It’s interface is voice controlled and––most importantly for our discussion––Amazon’s Alexa is integrated. Alexa is an RDA.

By moving the computation required for Alexa to the server side, Amazon can deploy Alexa almost anywhere. Alexa now is delivered via Bluetooth speakers, HDMI sticks, and by whatever the Core is. Auto integration is inevitable.

Amazon and others are incentivized to diversify their distribution to increase their ubiquity and the time you spend with your app. Further, new integrations bring new data, enabling better models.

Importantly, companies prioritizing machine learning are *not *incentivized to develop for the most powerful devices. Distribution of powerful, consumer devices is limited due to it’s expense and newness, limiting it’s value to RDAs which require massive pools of users. Expect device computing power to stagnate as the industry focuses on diverse, ubiquitous, cheap devices rather than powerful ones.

The Business Implications of Machine Learning

To recap, this is how machine and deep learning investment will likely impact the tech industry:

- Winners Will Win More: Existing big players like Facebook and Google have a massive advantage. They have tons of users, tons of their time, and war chests filled with both training data and money. Competing with these companies head on, creating the same training data they generate, is futile.

- Successful Startups Will Create Unique Training Data: Challengers can negate much of Google and Facebook’s advantages by pursuing new frontiers of training data. This can involve mobile apps, but will often involve new hardware to bring RDAs to new contexts. Successful challengers might build such a beachhead and be acquired for it before they ever get to develop models (see: Nest). The hard part for these companies will be transitioning from developing a product that generates lots of unique, good training data to building unique RDAs to generate and maintain velocity.

- RDAs are a New Network Effect Model: As RDAs emerge and mature, companies and investors will better understand how RDAs can build business models with network effects. Once there’s a clear example, the same explosion of marketplace business (“Uber for X”) and social companies (“Facebook for X”) will occur for machine learning start ups.

- Machine Learning Will Accelerate the Internet of Things: Hardware capabilities will stagnate but form factors will diversify. Computers will colonize every context that can fit sensors and network connectivity in search of training data.